A Decade (and a Bit) of Digital Merger Reviews in Europe

Competition policy in digital markets has been high on the policy agenda for some time now. Many jurisdictions have commissioned policy papers, investigating the particular competition issues arising in and potential shortfalls of existing competition enforcement in these markets. Following on from these papers, we are now seeing amendments to guidelines and laws emerging.

On the merger front, key concerns have been around “killer acquisitions” (or more generally, incumbent firms hampering dynamic competition and innovation) and around further concentration of consumer (big) data in the hands of a few. This has caused jurisdictions to lower notification thresholds; to more thoroughly investigate counterfactuals in dynamically evolving markets; to focus more on non-price competition; to re-evaluate market definition, in particular taking into account feedback loops between different sides of platform markets; and to properly assess the role data plays in the acquisition rationale. Most recently, the Competition and Market Authority (CMA), the Bundeskartellamt (BKartA) and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) have issued a joint statement, re-enforcing their commitment to effective merger control “in the face of high levels of concentration across various markets in the UK, Australia and Germany and a marked increase in the number of merger reviews involving dynamic and fast-paced markets“. Many of these markets are digital.

As an empirical person, I always like to confirm that the buzz around a topic corresponds to its actual importance in hard data. So, I started looking for statistics on digital merger reviews. While reviews of concentrations involving one of GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft) - or the absence of them - have received considerable attention, I am only aware of a few anecdotal studies on digital merger investigations in Europe more generally.* So I had a look at cases myself. This posed several challenges – in particular, as I had not expected to find that many potentially relevant cases. The graphs below summarise which ones I eventually considered relevant. There are a lot of such cases, across a large range of different segments and competition authorities have looked at a fair number of them in detail.

If you want to know more about which cases I chose to include in my overview, read on below the graphs. As always, I am looking forward to a lively discussion. Also email to understand what else can be done with the underlying database, to answer some more specific questions you might have, as I am in the process of collecting some further details on these cases.

What qualifies as a digital market merger?

This depends to some degree on the research question.

As a guiding principal I cast my net wide. This allows for different scopes going forward. Furthermore, I categorise each merger according to the end customer, the industry and/or the type of product the acquisition target’s main activity is focused on as this might assist in choosing cases which are relevant for the question at hand.

For an investigation to be included in my digital market merger review database, either the acquirer or the target must have a digital market focus. As the acquirer’s digital market focus at the time of the merger can be hard to establish and as I would like to capture the acquisitions potentially leading up to a prominent role in a digital market, the assessment is (mostly) made on whether such a focus exist today.

I elaborate on what a digital market focus means further below, when describing the individual categories. Broadly speaking, one of the merging parties should either provide a digital platform (including digital ecosystems) or engage in big data analytics. This is where most of the commercial opportunities of “new” digital technologies (as compared to more traditional information and communication technologies (ICT)) seem to have arisen. They also raise broadly similar competition concerns:

Positive feedback loops (driven by network effects and scale economies more generally) and economies of scope incentivise digital platforms to grow big and extend their scope into adjacent areas. Big data analytics can also benefit from size – more (volume, velocity, variety of) data leads to more precise analysis.

Both digital platforms and big data analytics commercialise data to some degree. This can require new payment models as data is non-rival and produced at almost zero costs.

Both rely on rather complex technology and customers might find it harder to exercise control than in traditional markets (bounded rationality).

Both, are also very innovative and dynamic, requiring an assessment of where the market is heading absent the merger (dynamic counterfactual).

Digital platforms are also plagued by other market imperfections (such as imperfect or asymmetric information, externalities and commitment problems), which can lead to market failure.

There are a few very active categories and players, where I had to make more judgement calls than elsewhere and therefore applied a more categorial rule:

Consumer finance payment mergers: Digital payment platforms are clearly part of the overview. However, there are a lot of payment related merger investigations and it was not clear in each individual case whether the acquisition contributed to the acquires digital market strategy. This also, as many of these cases are private equity led. To avoid too many ambiguous decisions, I therefore included a case when in doubt.

B2B software and hardware mergers: This category is particularly tricky, as I would like to draw a line between more traditional ICT and “new” ones. Offering the software or hardware as a service (“aaS”), is in my view one of the characteristic properties distinguishing old from new ICT. Today’s successful players in this area also focus on building technological ecosystems, providing several parts of the IT stack jointly.

B2B healthcare mergers: While healthcare markets more generally share some of the same competition issues as digital markets, in particular regarding dynamic counterfactuals, other aspects such as network effects, coordination and big data related issues are not always as relevant. For now, I include healthcare mergers with GAFAM as a merging party or those which are related to health data intelligence. Mergers involving pharmaceuticals, medical instruments or diagnostics, on the other hand, are excluded for now as it could not be established from the decisions that the merging parties’ technologies relied on big data analytics or that they provided a platform service.

Media mergers: There have been plenty of merger reviews in the telecommunication, TV and radio sectors. It was my impression that most of these dealt predominately with traditional infrastructure or linear content transmission and therefore did not qualify. It is, however, possibly, that these are steppingstones for a consolidation in the sector to allow for more effective competition of traditional incumbents with new players like Netflix. I am looking forward to hearing your thoughts on this. For now, these cases are excluded.

All merger reviews including GAFAM as a party are included. (As would be those including Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent - BAT - had there been any reviews.)

Several of the more traditional big technology companies have moved into offering their hardware or software aaS and are establishing themselves as broad solutions providers (or digital ecosystems). These moves have partly been achieved by merging with more specialist providers over the years. To capture this process, I err on the side of including acquisitions by IBM, Cisco Systems, Dell Technologies, Hewlett Packard Enterprise (and predecessors), Oracle and SAP.

How to find the relevant investigations?

Here it gets rather labour intensive.

DG Competition (DGComp) provides a detailed database on all notifications and corresponding decisions. Unfortunately, the industry classification (NACE), which is provided, does not allow to select relevant cases. Instead I employed a heuristic approach. Merging parties’ names and NACE codes were used to pre-screen the decisions. Case references in relevant decisions and detailed descriptions of affected products and issues in decisions more generally finally allowed me to identify what I believe should be a fairly comprehensive list of relevant phase 1 and phase 2 investigations, at least in the B2C / C2C segment. (I excluded simplified procedures as the available documents did not always allow to make the required judgement call.)

The CMA has a similar database and I employed a roughly similar procedure. Again, I believe I should have a fairly complete list of relevant cases investigated by the CMA or its predecessors in phase 1 or 2.

The BKartA publishes formal decisions for phase 2 merger investigations only. These have all been screened and included where relevant. It also publishes case studies for selected phase 1 merger investigations. I added these to my database as well. When comparing cases to other agencies it should be kept in mind that the BKartA ones are likely less complete as not all phase 1 merger investigations might have been published.

Among the national competition authorities in Europe, the CMA and the BKartA have been quite vocal in the area of digital markets. Given time constraints and limited language capabilities, I therefore chose to focus my research on these two. I am very interested in hearing your views on relevant cases in other jurisdictions.

When to start?

I decided to start in 2008, to include the Google / DoubleClick merger. While there are some relevant B2B / C2C cases prior to this date (e.g. Bertelsmann / Burda - HOS Lifeline, Vodafone / Vivendy / Canal Plus, Travelport / Worldspan), these are few and far apart. I might miss more relevant cases in the B2B sector due to this cut-off date. However, the further I go back, the more I will include hardware and software mergers which focus on more traditional ICT. 2008 therefore appeared to be a sensible comprise.

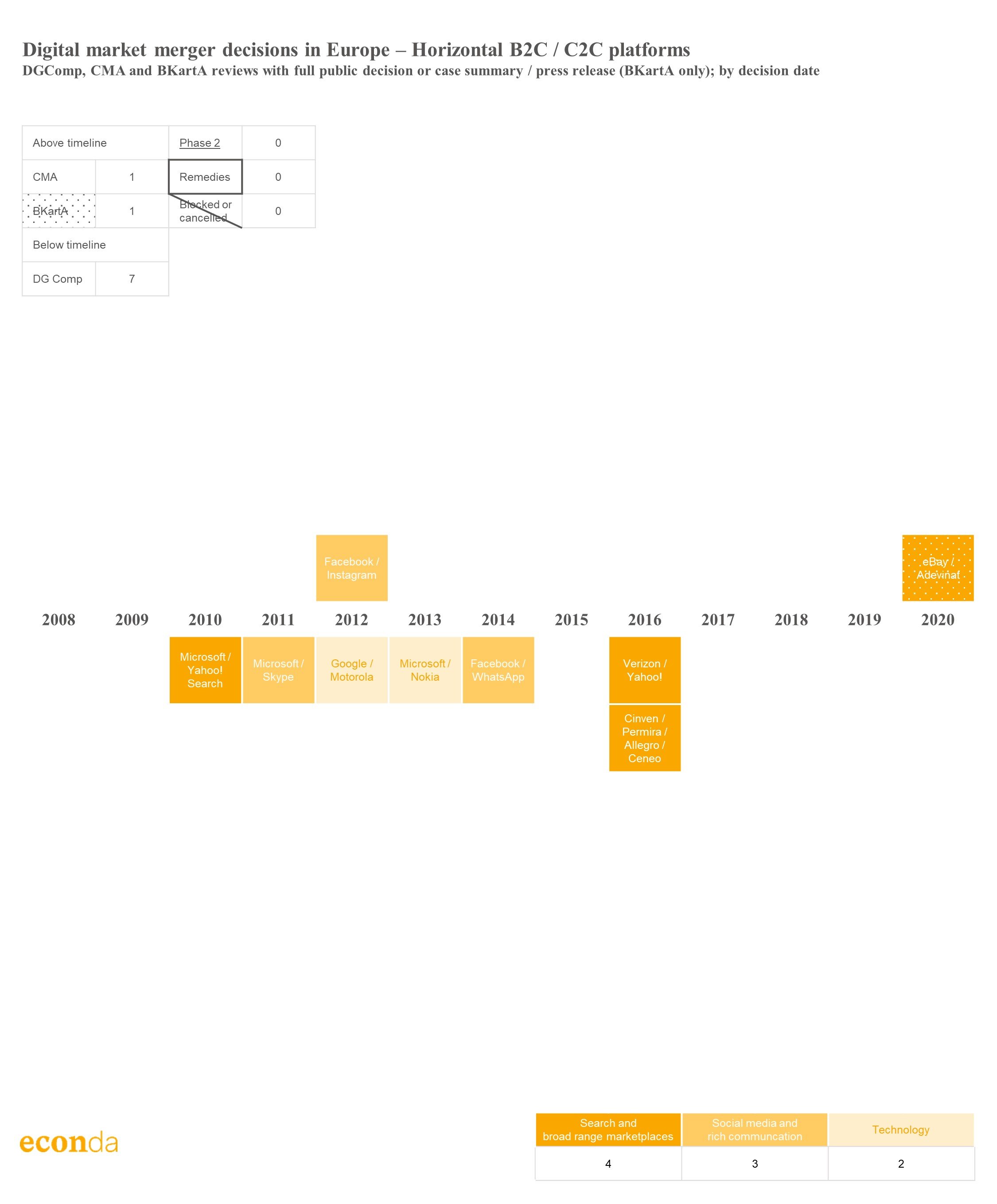

Horizontal B2C / C2C platforms

The most obvious first category of digital markets to include are consumer oriented horizontal digital platforms. These facilitate digital content and exchange at distance of products between businesses and consumers (B2C) or among consumers (C2C), without having a particular industry focus. Among these fall online general search providers and broad range marketplaces as well as (rich) digital communication providers and social media. I also include technology platforms which match application programmers to consumers or more generally provide a digital ecosystem.

I do not count telecommunication providers or producers of the hardware used by consumers to access digital services (e.g. computers or mobile devices) as having a digital market focus, unless provided as a service or as part of a wider digital ecosystem. Equally, general purpose software is only included if it has developed into a digital ecosystem (such as Android).

Surprisingly few merger investigations fall into this category (9 in total). Apart from 2, all are reviewed by DG Comp and all have been cleared in phase 1. However, with Facebook / Instagram (CMA) and Facebook / WhatsApp (DG Comp), two of the most widely discussed and contentious digital market merger decisions fall into this category.

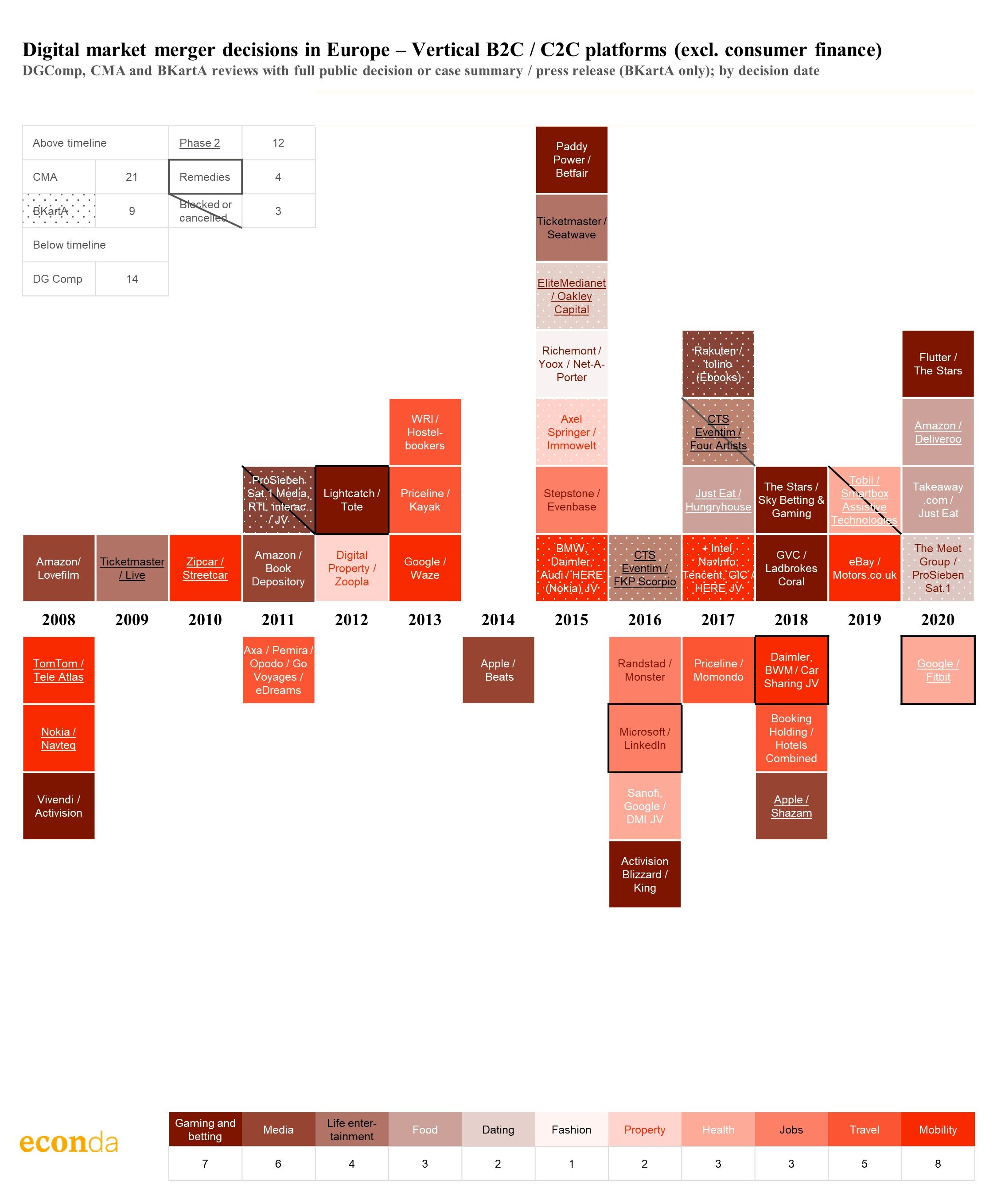

Vertical B2C / C2C platforms

Next on the list are vertical B2C or C2C platforms. These platforms have an industry focus.

Here is gets very busy, in particular for the CMA. In total, I count 44 such merger reviews. Other than with horizontal platforms, the share of the national competition authorities is rather high (48% CMA and 20% BKartA).

A fairly large number of all cases (27%) have been investigated in depth and the authorities have intervened (requesting remedies or blocking the merger altogether, including cases cancelled in phase 2) in a number of them (7 out of 44).

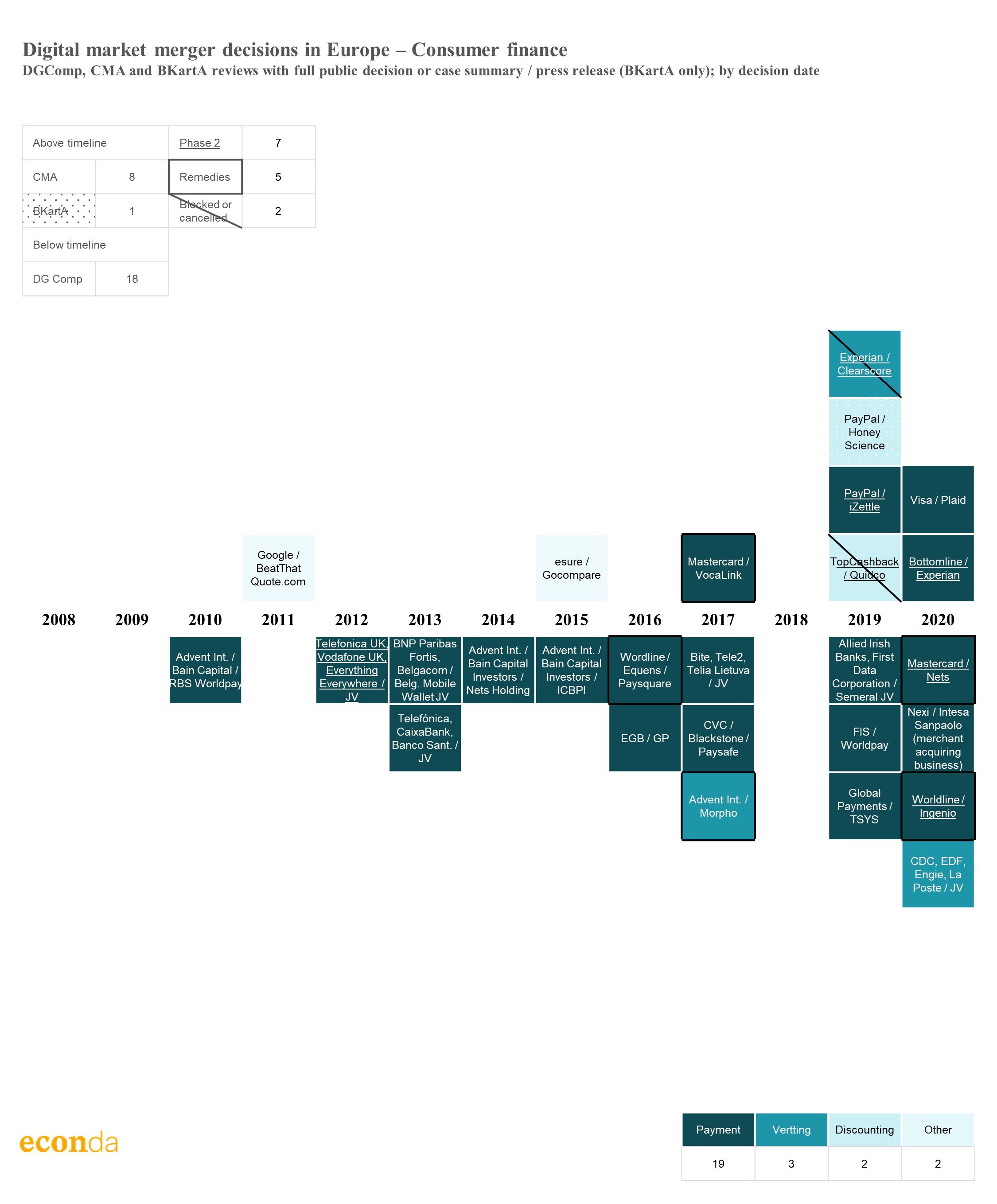

Consumer finance

I singled out consumer finance as I encountered a lot of (and as discussed above, more ambiguous) related cases.

DGComp alone investigated 18 such cases, while the CMA looked at 8 and the BKartA at at least one.

26% of the cases were investigated in detail, and in 26% of the cases the authorities intervened.

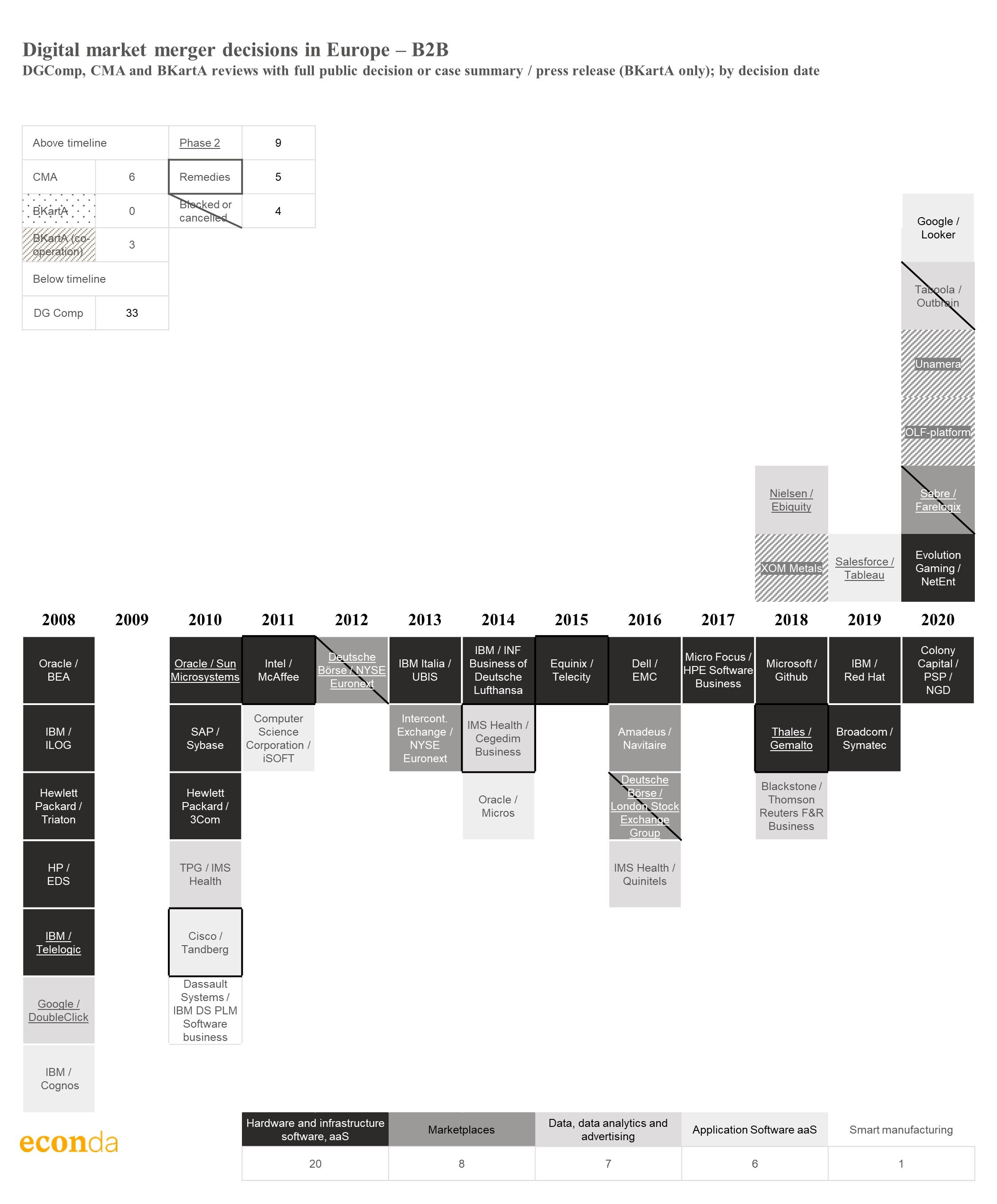

B2B

I divide firms operating in business-to-business (B2B) digital markets into those offering (i) marketplaces; (ii) infrastructure and closely related software (also referred to as “infrastructure software” and including operating systems, databases and middleware) aaS; (iii) application software (including enterprise application software and software for individual productivity) aaS; (iv) data, data analytics and advertising; and (v) smart manufacturing.

I identified many such cases, with hardware and infrastructure software aaS accounting for by far the largest share among these (20 out of 42).

Also, many of the identified B2B merger reviews happen surprisingly early in my observational period. (As discussed above this might mean that I am potentially missing relevant investigations before.) This is different in the B2C / C2C segment, where cases overall increase over time.

In B2B it was more difficult to decide whether a merger review qualifies as digital market related or not than in B2C / C2C and I would therefore be less confident as to how complete my overview is. Again, I am keen to hear your views. Still, I think the overview above illustrates that the digital market strategies of the larger B2B players are at least partly built on acquisitions.

From the reviews I identified (42 in total), most were investigated by DGComp (79%). With 20% second phase investigations and 20% interventions, there also was a fair amount of attention paid to these mergers.

* E.g. Ex-post Assessment of Merger Control Decisions in Digital Markets commissioned by the CMA, cases pointent out in a speech by Andrea Coscelli (CMA) and cases listed on the BKartA website discussing their digital markets’ strategy.